From GaN to Magnetics: How Jovana Plavšić Builds Hardware with Curiosity and Precision

Engineering is not just a career, it’s a way of seeing and shaping the world.

From Fixing Things to Designing Systems

“I grew up in a small town next to Belgrade. My father was a mechanical engineer, my grandfather was a mechanic. From the youngest age, I remember fixing things up. That was where my spark for research and fixing started.”

When Jovana Plavšić tells her story, it’s clear that curiosity wasn’t a hobby — it was the family language. She describes her childhood in Serbia not in terms of limitations but as an environment rich with mechanical influence. That early exposure shaped her choice to study electrical engineering at the University of Belgrade, one of the region’s most respected programs.

She gravitated toward power electronics, a discipline that demanded both theory and tinkering. “Physics and biology were my favorite subjects in high school, but in university, I decided to jump into electrical engineering. I loved it,” she says.

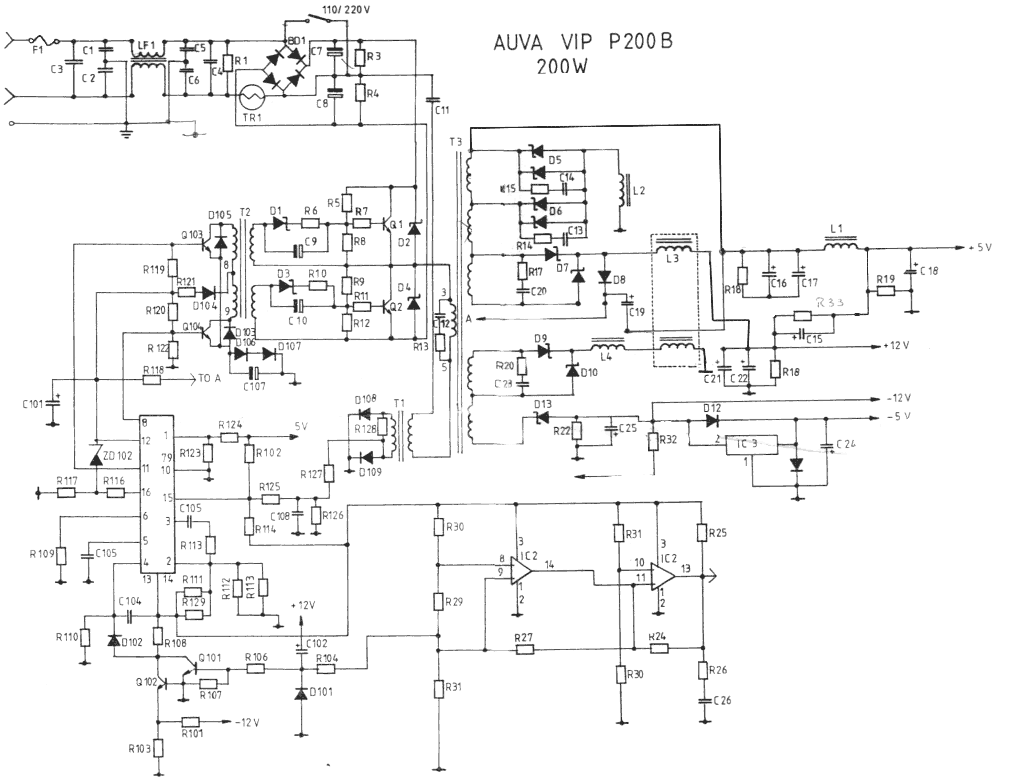

Her entry point was the student research group H-Bridges, where she immersed herself in real-world projects. “We had a project that lasted two years during COVID. It was about an LLC topology, which is now a really hot topic in power electronics. I helped design a high-frequency transformer — I don’t think many people at the faculty had done that before.”

That experience gave her a taste of applied research and confirmed that her path was going to be hands-on, experimental, and deeply hardware-rich.

Choosing Small Teams Over Corporations

After graduating, Jovana made a decision that would shape her career trajectory. “I focused more on small companies because corporations or bigger companies are usually focused more on software. The research part is missing. It’s only doing the same thing over and over again.”

She found her home at Sense and Drive, a small Serbian company specializing in advanced power electronics and power converters. She started as one of just two employees; today, they are a team of four. The small size has been an advantage, allowing her to learn fast and stretch beyond narrow roles.

Her CEO, Milan, has been critical to that growth. “He’s an engineer himself and he has talent for making engineers comfortable — which is not really a talent many have in general. He knows when you need time to understand something, and when he needs to push you forward. He’s been in my shoes.”

With that foundation, she and her colleagues broadened their portfolio, balancing client projects with the development of their first product: PERK (Power Electronics Research Kit).

“We’re making a kit with modules for switching, sensing, and control so you can easily test out different topologies to measure and control the system. It’s exciting because we’re using the knowledge we gained from projects we’ve done, but we’re also making testing equipment. That’s a totally different perspective — you need to know when to push and when to pull.”

For Jovana, PERK is more than a tool. It’s a way of democratizing prototyping for students, researchers, and small labs that don’t have access to expansive infrastructure.

The Challenge of Defining an MVP

Building a product as engineers for engineers presents unique challenges. “It’s difficult for us to understand what MVP is, because most engineers like to plug it in and for it to play. But this is a research hub, with modules. You need to be a researcher. We know the topic so well that sometimes we (I hope that mostly we can think like a customer) can’t just step back and think like a customer.”

Her awareness of this tension grew when she attended MIT’s 24 Steps for Entrepreneurship seminar. “I was maybe the only female engineer in the room. Bill Aulet asked questions and I always had the wrong answers. He laughed and said, ‘You’re an engineer, right? Classic.’ For me, technology is important. But they kept reminding me: the market and customer are important too.”

This duality — engineering rigor versus customer adoption — has become a central part of her philosophy. “For different kinds of things there are different customers, and you need to know the profile. For us, the customer is also a power electronics engineer. That makes it easier in some ways, but harder in others. We know too much.”

Power Optimization: Shrinking, Switching, and Systems Thinking

When the conversation turns to power optimization, Jovana becomes animated. This is where her professional expertise shines.

“There is a big application of high-voltage GaN in electric vehicles. It could significantly reduce the size of the charger and the power electronics part of it. To size down your converter, you need to switch at higher frequency, so the passive elements — which are the biggest part of the converter — become smaller. But a lot of different aspects of the design don’t work together well because of the technology, materials, and so on.”

This systems-level perspective is exactly what separates hardware-rich engineers from component-level thinkers. She is not dazzled by GaN or SiC alone — she insists on understanding how magnetics, topologies, and tradeoffs intersect.

“The magnetic part of the converter is really interesting for me. New materials that are coming into magnetics are really important. You can’t just think one variable at a time. It’s good to think all around the problem, not just solve it straight away because the internet says this is the right thing to do.”

She cites the work of Professor Vasic at Politecnico de Madrid, who has been experimenting with advanced 3D-printed materials for magnetics. They’re not commercial yet. 3D printed materials are being used at laboratories around the world. She talks about how these will probably will become commercial in the next five or ten years but more so she speaks about this shows how much more there is to explore beyond semiconductors.

This aligns with voices like Johann Kolar (ETH Zurich), who has long argued that the future of power optimization lies in co-design: semiconductors, magnetics, cooling, and control working in tandem. Similarly, Alex Lidow (EPC) emphasizes that GaN’s true potential is unlocked only when designers think holistically at the system level.

Jovana’s perspective is a lived version of these principles. She is designing, testing, and optimizing not just for efficiency but for balance across constraints.

Transparent Timelines, Honest Engineering

Jovana is equally candid about project management in engineering. “I noticed a race with time. Some companies give timelines that are half what’s realistic. I don’t understand how. Maybe they have huge teams. But even then, production takes time, assembly takes time, delivery takes time, meetings take time. You can’t skip those.”

Her approach is rooted in honesty. “We were really open with customers. We’d say: this takes this time. If you want to work with us, we’ll do it well. That honesty built trust.”

In a hardware world where speed-to-market is worshipped, Jovana offers a reminder: realism is not laziness, it’s leadership.

Women in Engineering: Standing Out by Asking

At her first major trade show in Nuremberg, Jovana recalls, “I went with pink lipstick, and people thought I was giving out refreshments. But when I asked difficult technical questions about modules and topologies, they realized I wasn’t just there as staff. I was there as an engineer.”

This moment illustrates both the obstacles and the opportunities women face in hardware. “There are a lot of women in power electronics engineering in Serbia. In my university group, we were like a girl gang — many are now PhDs or working abroad. But in industry, especially power electronics, I often find myself the only woman in the meeting.”

Her approach is not to complain but to show up with questions.

“I can be really demanding in the answers I want, especially when it’s something I worked on. Maybe it makes me annoying. But I think it makes me stand out.”

Her story underscores why the field needs more women. Diverse perspectives aren’t just a moral imperative; they change the way problems are defined. As she puts it: “When you have six perspectives on a problem, sometimes the eighth one is the right one. That’s why we need more voices.”

Designing for Repeatability and Rethinking MVPs

Jovana is candid about the difference between designing solutions and designing tools. “We’re using the knowledge we gained from all our projects,” she says, “but when you design testing equipment, you’re forced into a completely different perspective. Suddenly you have to think about usability, repeatability, and the whole research process itself—not just solving a problem once.”

That shift—from one-time solution to repeatable platform—requires a new kind of empathy. It is not enough that the circuit works; it must work in the hands of others, under varied conditions, producing reliable and comparable results. This demand echoes a truth that many leaders in power electronics and test engineering have emphasized: the future belongs to tools that accelerate learning, not just finished products.

But designing tools also collides with the culture of minimum viable products (MVPs).

“In MVPs, engineers want something that works perfectly—customers often just want proof it works at all. That disconnect is hard to accept as an engineer, but once you see it, you understand why companies push for quick prototypes rather than long, polished builds.”

This tension defines the heartbeat of hardware innovation. Engineers are trained to value elegance, robustness, and verification. Markets, on the other hand, often reward speed, iteration, and visible traction. Bridging that divide requires humility: to accept that a rough, working prototype can sometimes create more value than a perfect design delayed by months.

For Jovana, this realization does not diminish engineering—it broadens it. It demands a mindset where engineers are not only builders but translators, turning hard-won technical knowledge into tools and prototypes that help others move faster. In that sense, hardware-rich development is as much about empowering process as delivering outcomes.

Curiosity as a Way of Life

Jovana resists the neat answers when asked about balance. “I don’t know if I answered your question,” she laughs. “I just like it. I feel grateful. I had the opportunity to meet amazing people around the world who are at the top of research in power electronics. That makes me grateful.”

For her, curiosity is both discipline and compass. She networks widely, attends summer schools with Infineon in Austria, joins MIT workshops, even engages in civic issues at home. “Now is the time to be wild. When you’re young, take risks. Say yes.”

She sees curiosity not only as a personal trait but as an engineering necessity.

“Perspective on the problem you’re solving is always up for discussion. Maybe six perspectives are wrong, but the seventh one is the right one. It’s always good to hear another.”

Engineering and Society

At the end of our conversation, Jovana shifts from engineering to politics. She talks about the tragic collapse of a train station roof in Serbia, which killed 16 people, and the student-led protests demanding accountability.

“It’s really important for all people in Serbia — even in the most eastern or western village — to be eager to find out the truth. To have real institutions that do their job. To take down an entire corrupt system so our children have a better future.”

For Jovana, engineering is not separate from society. The same values that make her insist on realistic project timelines or honest optimization — transparency, accountability, curiosity — are the values she demands of her country’s leaders.

Closing Reflections

Jovana Plavšić is a reminder that the next generation of hardware leaders is not only technically sharp but philosophically grounded.

She is shaping systems with GaN, SiC, and advanced magnetics. She is building products that make research more accessible. She is advocating, through her presence and her questions, for more women in the field. And she is refusing to separate engineering from the broader human systems in which it operates.

“Engineering is not just a career,” she says. “It’s a way of seeing and shaping the world.”

Her invitation to the rest of us is simple: be wild while you can, take risks, stay curious — and build with honesty.